The media reacted as if the ex-recorder won his defamation suit against Lake. The facts suggest it was at best a draw.

Will former Maricopa County Recorder Stephen Richer be buying a resort in the Cayman Islands soon? That might be the easiest way to tell how much dough he raked in after settling his defamation suit against Kari Lake.

Here’s my guess on that point: “little or none.”

Over the past four years, the droll, ginger-headed Republican became one of the mainstream media’s favorite political figures. Voted into office in 2020, just as Donald Trump was voted out, Richer built a reputation for pushing back against the election deniers in the MAGA wing of his party, often via patient retorts on his X account. For that, he got love aplenty from the press — from Politico, Time Magazine, 60 Minutes, PBS, Wired and even Phoenix New Times, which last year named him “Best Republican.”

I give Richer points for standing up for “election integrity” — though wasn’t that, like, his job? — but the constant lapdog-like fawning from my fellow journalists was annoying in the extreme. Particularly when it comes to his much-ballyhooed lawsuit against Lake.

A refresher on the saga, if you need it: In 2022, Lake lost her gubernatorial race to Democrat Katie Hobbs, a setback Lake handled by characteristically spouting off a stream of crackpot conspiracy theories about the election. In 2023 Richer sued over Lake’s claims that he intentionally printed 19-inch images on 20-inch ballots so that tabulating machines would reject them and that he injected 300,000 “unlawful early voting ballots” into the election day vote count.

Lake’s claims were disprovable bullshit, to be sure, as many news outlets pointed out at the time. While other politicians in Lake’s crosshairs (including then-County Supervisor Bill Gates) let the marketplace of ideas sort things out, Richer took Lake to court. Lake unsuccessfully tried to get the suit dismissed and then stopped defending it last March, which meant she legally admitted liability. Richer and Lake then haggled for months over damages.

Then, in November, the Washington Post surprised many with an apparent scoop, headlined: “Kari Lake settles election defamation case brought by Arizona official.” In a text message, Richer told the Post that “both sides are satisfied with the result.” A day later, Arizona Republic columnist EJ Montini wondered “how much richer-er” Richer had become, observing that the settlement terms were confidential.

The implication was clear: Lake lost, Richer won. End of story.

Nope. First of all, it wasn’t over. Two days before Christmas, Richer’s attorneys filed a stipulation agreeing to a dismissal “as to all parties with prejudice, with each party to bear its own fees and costs.” On Jan. 6, Maricopa County Superior Court Judge Randall Warner signed an order to this effect.

Second, it’s not clear that Richer won anything. Warner did not mandate that Lake issue an apology, nor did he require that she retract her prior statements. There was no determination of damages — at least publicly. Most tellingly, Richer handled his own attorneys’ fees. So how exactly did Richer “win”?

And why was the media, which now fears reprisals from the incoming Donald Trump administration, so eager to cheerlead an elected official filing a lawsuit so clearly at odds with the spirit of the First Amendment?

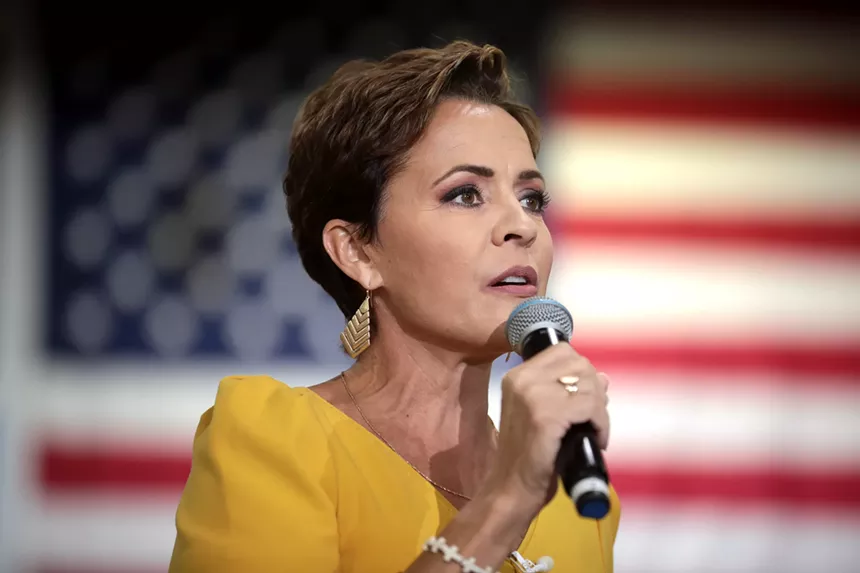

Gage Skidmore/Flickr/CC BY-SA 2.0

Devil’s advocate

In an X post on Jan. 7, the day after Warner dismissed Richer’s complaint, Richer decried those who objected to his suit against Lake on First Amendment grounds but have remained silent about Trump’s suit against an Iowa pollster who incorrectly forecast Trump would lose the 2024 election in the state. Richer also implied that he prevailed in his suit over Lake.

“Heard a lot about ‘lawfare’ and ‘suppressing the First Amendment’ when I filed a suit against Kari Lake for her specific, demonstrably-false, no-basis-in-reality, lunatic-level claims about the 2022 election,” he wrote. He complained that he hadn’t “seen those same people” posting about Trump’s suit.

“Hint: it’s never about actual law or about principles,” he added. He noted that “Kari’s two motions to dismiss lost at the trial court . . . She later defaulted on liability.”

Lake did default, asking the court to move on to the money she would have to fork over to Richer as a result. “I look forward to entering the damages phase of this case,” Richer said in a press statement at the time. He mentioned an “endless barrage of threats” he said he received due to Lake’s statements and the resulting mental anguish he and his family endured.

The case entered a contentious discovery process. Two days before the Post reported the settlement, Richer was still seeking “general and punitive damages” for the “distress” and reputational harm Lake’s invective ostensibly caused him. Then the “settlement” bombshell dropped. But it’s not clear if Richer got anything.

The lawyers involved are largely mum. Protect Democracy, the deep-pocketed, progressive nonprofit backing Richer’s suit, did not respond to my request for comment. Daniel Maynard, Richer’s Phoenix-based attorney, said: “I can’t get into what the settlement is because it’s confidential.” Maynard refused to say who, if anyone, was paying him. He did state that Protect Democracy wasn’t footing his bills. When I reached Richer via text, he said he had nothing to add beyond what Maynard told me.

Lake’s attorney, Dennis Wilenchik, wrote via email, “We are pleased the matter was resolved without the need for further wasteful litigation.” He added that Lake “has not withdrawn any statements.” He said he could not comment further on the settlement’s terms.

A cursory review of Lake’s social media activity shows that she continues to engage in election denialism. Her feed still contains critical comments about Richer, including a November X post accusing Richer of “destroying evidence” and “refusing to comply with discovery,” which Richer’s attorneys disputed in court filings.

In his original lawsuit against Lake, Richer asked for a laundry list of goodies: “attorneys fees,” “costs of the suit,” “prejudgment and post judgment interest at the highest lawful rates,” “declaratory relief” from the court stating that Lake’s statements were false, and “injunctive relief” ordering Lake to remove any defamatory statements. If Richer didn’t get the attorneys’ fees, it seems unlikely he got anything else.

That’s the interpretation of famed First Amendment attorney Marc Randazza of the Las Vegas-based Randazza Law Group. Randazza has been involved in countless defamation cases over the years. “Most court cases end with a whimper, not a bang,” he said. “It’s very common for the stipulated dismissal to say everybody bears their own costs and fees.”

But Randazza added that the fact there’s “not even a milquetoast retraction” from Lakeraises his eyebrow. Randazza said he has worked on cases that dragged endlessly as the parties wrangled over what each would say after the suit. As for damages, Randazza observed, Richer still had to prove Lake’s accusations caused him harm. That would be tough since Republicans were pissed at him long before Lake piled on.

Richer was elected county recorder in 2020 and was openly contemptuous of Trump and the “Stop the Steal” movement. That stance made him a hero to Democrats and to the GOP’s never-Trumpers, but anathema to the MAGA faithful. Death threats? Sure, Richer got ’em. He also got ’em before Lake blamed Richer and others for her own shortcomings.

Plus, any “damage” to his rep was easily offset by the gushy plaudits from the media. Indeed, Richer now writes opinion pieces for the largest newspaper in the state.

“If you asked me to gamble on what actually happened in this case,” Randazza told me, “I wouldn’t put five bucks up that says money changed hands in either direction.”

Marc Randazza/Wikimedia Commons/CC BY-SA 4.0

SLAPP happy

In the grand scheme, Lake and Richer both emerged from their fracas as losers. Richer got spanked in the GOP primary by MAGA-ite Justin Heap, who won the general election. Lake ran a crappy campaign for U.S. Senate and got her backside handed to her by Democrat Ruben Gallego, a loss that she hasn’t been so vociferous in disputing. She may or may not wind up leading the state media entity Voice of America for Trump.

Hopefully, she puts up more of a fight for free speech in that role than she did in her court battle with Richer. When pols start suing people for defamation, it can have a chilling effect. None other than the U.S. Supreme Court said as much in the landmark 1964 case New York Times v. Sullivan.

Early in Richer’s and Lake’s legal battle, the First Amendment Clinic at Arizona State University’s Sandra Day O’Connor College of Law got involved, asking the court to dismiss Richer’s suit based on a recently rewritten anti-SLAPP law in Arizona. SLAPP stands for “strategic lawsuits against public participation.” Historically public figures and wealthy plaintiffs have used such suits to muzzle criticism by the press and others.

Under the Arizona law, a “state actor” such as Richer should be held to a higher standard when it comes to defamation. Though Richer took pains to note that he brought the complaint in a personal capacity, First Amendment Clinic director Gregg Leslie told me Richer was “nonetheless a public official bringing a libel case.”

The lower court ruled against the clinic and the Court of Appeals declined to take the case. Ditto the state Supreme Court. Though the Republic and the social media peanut gallery slammed ASU’s clinic for making the argument, Leslie believes he and his law-student staffers “were doing the right thing by trying to help it get dismissed.”

Some commentators were aghast that Leslie’s clinic weighed in on Lake’s side, as if to do so was beyond the pale. But Randazza — who has repped porn platforms, Satanists, Nazis, Alex Jones and more — praised the First Amendment Clinic as one of the finest in the country.

“That’s what the First Amendment is: a neutral principle,” Randazza explained. “Man, my client list is worse than the guest list at Mos Eisley. And I’m proud to have represented every single one of ’em.”

Leslie said he has no regrets about taking the Lake case. When the heat was on, he recalled, some ASU faculty would stop by and ask him if he was OK.

“Yeah,” he told them. “If you’re a First Amendment advocate, you live for a case like this.”

Even Maynard, Richer’s mouthpiece and an old First Amendment hand, thinks Leslie and his ASU clinic were correct in taking up for Lake in principle, calling it a “good opportunity” for the law students involved, though he still thinks they were wrong on the law.

What would he say to the naysayers who pooh-poohed the clinic?

“What the hell? That’s what they’re supposed to do,” Maynard replied. After all, he added, “this is a First Amendment issue.”